A Son on His Father

BY RICK MAJERUS

My father had the most expressive eyes. They were blue eyes that seemed to have a life of their own. They were able to fix and focus on friend and foe alike. They were always riveted with an attentive stare to an injustice, transgressor or simple indignity that the working man he was-he represented-found most reprehensible.

These were eyes that had seen, aided and abetted the ascendency to power the like of John F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter. As secretary-treasurer of the once powerful United Auto Workers, these eyes watched over the purse strings of union moneys that were divvied up for various political and social causes. These were eyes that gazed upon Robert Kennedy as he testified in the McClellan labor hearings. Eyes that marched and eyes that responded with steely resolve to the hated stares of the Ku Klux Klan as he traveled the streets of Selma, Ala., and the deep South. These were eyes opened to social injustice and acutely aware of the plight of black Americans as he marched with them in their struggle for equality and equal opportunity in the ’60s. These were eyes that had traveled every continent. Eyes ever watchful of a situation where a working man or woman may be exploited. These were eyes that had seen service to country in the Philippines. Eyes that had been to the last papal elevation as the official representative of the United States.

These were eyes that were “all over you babe” when it came to my mother. Perhaps in these situations they were most attentive of all. They were each other’s best friend and more trust, more kindness could not have been communicated than by the wonderful gaze he would visit upon my mother.

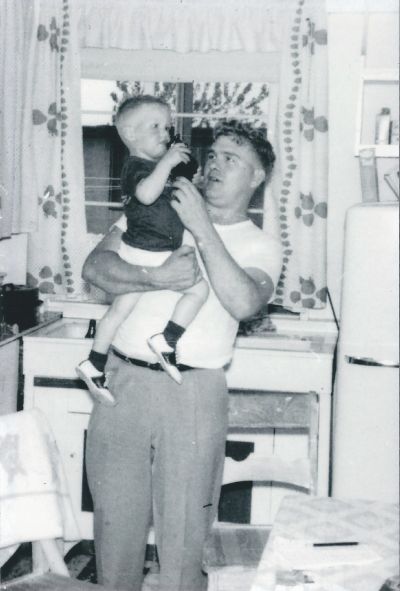

These were eyes that were proud to see all his children graduated from college with advanced degrees when his own eyes had not seen even the minimal pomp and circumstance of a high school graduation. They were eyes that welled with pride as his grandchildren were born. Eyes that were happiest at play with the little girls on a dirty carpet. The McDonnell Douglas and Boeing Corp. deals were always on hold because my mother couldn’t get him to take his eyes off those kids he loved more than life itself.

These were the eyes of a visionary. My father was at the forefront of the American labor movement in its greatest era. He ushered in the end of labor-management adversarial relationships when he negotiated American Motors contracts that were advantageous to both parties.

These were eyes that could see into the future of American education as he sat on the board of regents for the University of Wisconsin. He was able to see the mission of higher education as being one that must remain accessible to all economic brackets. That meant the working stiff like himself, who enameled the toilet on Kohler’s third could see a brighter future for his family by virtue of the fact his children, and children’s children, would have an opportunity to reach out for the brass ring- that prized piece of parchment.

My dad’s eyes had seen them come and seen them go. In his own world he was a bit of a kingmaker. These eyes witnessed upfront and firsthand the inaugurals of John F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter. They saw the “credentialed” ascend to senate and congressional seats and to judgeships. They stewarded the way for those he deemed deserving. Those who had compassion for the poor, empathy for the elderly, and the greater good of the working man and woman at the forefront of the agenda.

In my father’s eyes you saw love, care, compassion and concern not only for his immediate family but also for the family of man. His eyes never left the modest bungalows where the people-his people-lived. His eyes saw suburban America as a bit divisive and segregated.

His eyes fought the good fight as he chaired a parks and recreation commission, a harbor commission to keep the best lands of Lake Michigan forever free and clear from the developers who sought to make the best plots the exclusive province of the wealthy.

These eyes counted untold thousands for charitable contributions to cancer research, heart-fund calls and AIDS assistance. They saw his procurement of moneys for shelters and hospices, for public housing projects and homes for the elderly where they would live their later years in a dignity not necessarily predicated on the accumulation of worldly possessions.

They were good eyes, kind eyes and he often referred to himself as “Old Eagle Eye.” They had an uncanny knack to locate a lost barrette, a child’s marble or an important document necessary to finalize a negotiation. These were eyes that were seldom sad for he saw the best in people and he brought that out in them.

Now the man had some bad pipes and his heart wasn’t the best. It stopped beating five years ago to the day of this column. It was the kindest of hearts though. Those eyes never saw the movers and shakers, senators, judges, dignitaries and assorted figures in the world of labor, politics and sports that came to attend a simple memorial service for a man who never owned more than a modest home on a numbered street and drove a nondescript American car until the day the great heart ceased to beat.

We would like to have seen those eyes once modem all of us, the brothers of the United Auto Workers and my friends from the Little League. The guy and gal at Kohler, Master Lock, Ford, American Motors and Boeing who worked on a line but somehow could hold on to a dream and maybe see it to fruition because his eyes were visionary in regard to the most basic needs, wants and desires of those people he represented well and loved so.

No, none of us could look on those eyes and know them as they were because somebody else has them. In death, as in life, my father gave and his final gift was his organs and ultimately his body itself to a medical school.

My father paid heed to the Jewish sage Hillel who said so eloquently 2,000 years ago: “If I am for myself alone, what good am I?”

What better gift to give this Christmas than the only gift that will keep on giving. In memory or because of someone you love, check off your driver’s license and donate an organ.

The great heart of Raymond Majerus no longer beats, but his eyes continue to see. Consequently, someone will have the nicest Christmas. Perhaps they will look upon their family and friends as he did this holiday season. Because they are able to do so, they feel more fervently a love for one another that is the essence of the season. And if those eyes are seeing, happy and well with a touch of emotion and sense of all being well with the world, then somewhere “Old Eagle Eye” will not have died in vain.